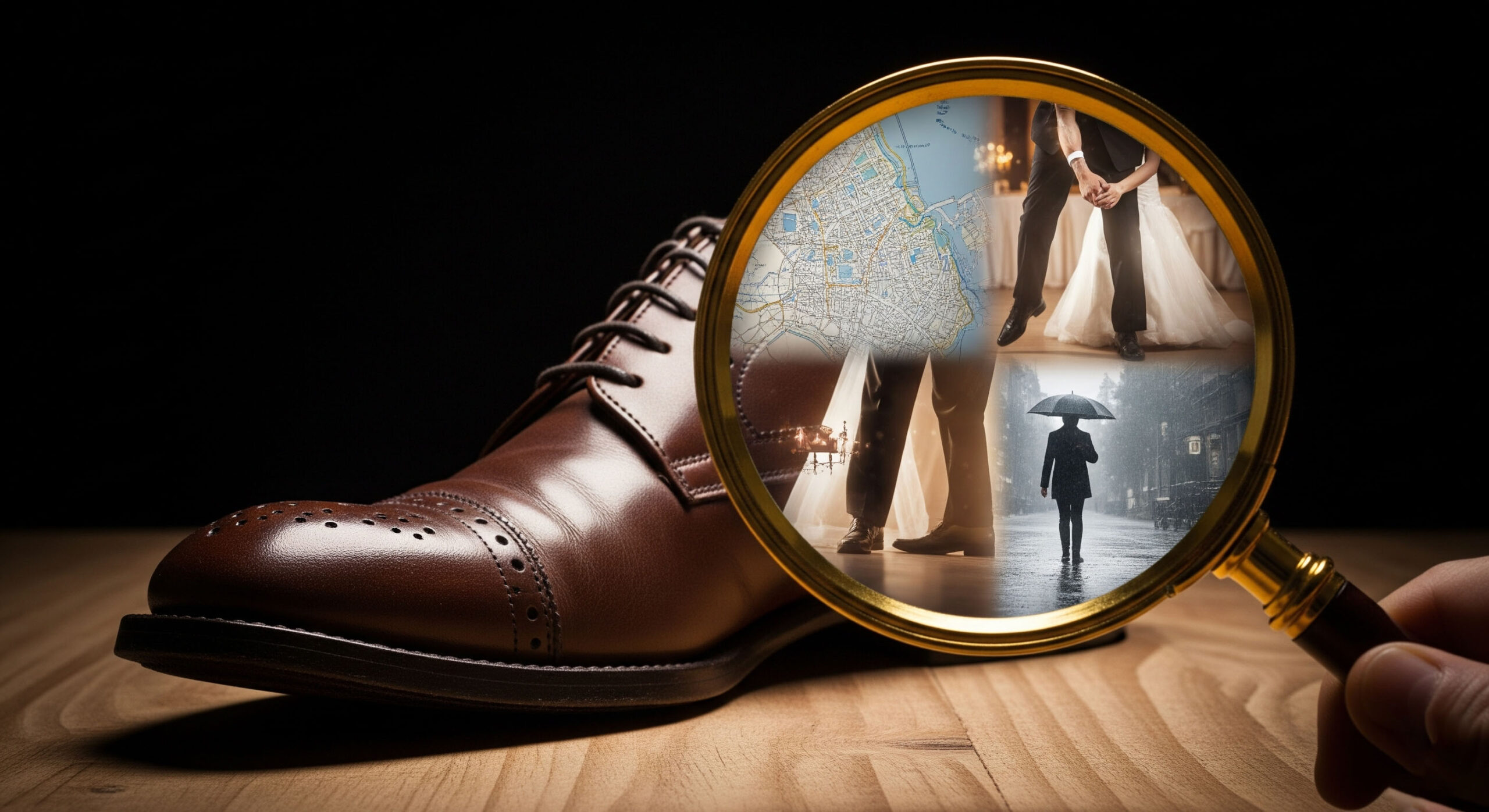

Before Sherlock Holmes ever captivated the world with his astonishing powers of deduction, there was a real man who seemed to possess the same magic. His name was Dr. Joseph Bell, a surgeon and professor at the University of Edinburgh in the 19th century. One of his students, a young Arthur Conan Doyle, was mesmerized by Dr. Bell’s uncanny ability to deduce a patient’s life story from a handful of simple, observable details before they even spoke a word.

What seemed like a superpower to others was, in fact, a systematic method. Dr. Bell had mastered the art of moving from simple seeing to deep understanding. He embodied the very phrase his student, Doyle, would later make famous in the mouth of Sherlock Holmes: “You see, but you do not observe.”

That single sentence contains the secret to his genius, and it’s a secret you can learn. The “Sherlock Scan” is not a fictional superpower; it’s a disciplined, three-step framework for thinking that can train your mind to see the rich stories hidden in the world all around you.

The 3-Step Sherlock Scan Framework

This framework, which I detail in my book, The Observation Effect, is a process for turning raw, visual data into profound insight. It moves you from passively seeing to actively analyzing.

Step 1: Observation (Gather the Raw Data)

This is the foundation of the entire process, and it is the step most people skip. True observation is the disciplined act of gathering facts from the world without premature judgment or interpretation. You are not looking for meaning yet; you are simply collecting clues. You must become a human camera.

- What you see: A scuff mark on the side of a person’s leather shoe.

- What you don’t do: Immediately jump to, “They must be clumsy.”

You simply note the fact: “Scuff mark, right shoe, outer side.” Your goal is to build a small collection of neutral, objective details. Notice the worn patch on a coat sleeve, the type of keychain they use, the dog-eared pages of the book they are carrying. Just the facts.

Step 2: Inference (Connect the Dots)

This is where your mind begins to work. Inference is the process of drawing logical connections between your observed facts. It’s the step from asking “What is it?” to asking “What might it mean?” An inference is not a wild guess; it is a reasonable possibility based on the evidence you’ve gathered.

- Observation: The person’s laptop is covered in stickers from various national parks.

- Inference: It is reasonable to infer that this person likely enjoys the outdoors, hiking, and traveling.

- Observation: A colleague’s coat sleeve is shiny and worn, and their fingertips have a faint ink stain.

- Inference: You can infer they engage in a great deal of writing, likely with a specific type of pen.

Step 3: Deduction (Build the Most Probable Story)

Deduction is the final and most creative step. It is the art of taking all your inferences and weaving them into the most probable story or hypothesis that elegantly explains all the data points. Sherlock Holmes would famously generate multiple possibilities and then eliminate them one by one until only the most likely truth remained.

Let’s use a modern example from my book to see the full 3-step process in action:

You’re in the office kitchen.

- Observation: You see a colleague who is normally a bit sluggish in the mornings. Today, they seem unusually cheerful and energetic. You also notice they are holding a coffee mug from a popular new artisanal cafe that just opened a few blocks away.

- Inference: You can infer they are trying a new coffee spot. You can also infer they are actively looking for a way to improve their morning energy levels.

- Deduction: The most probable story that connects these facts is that your colleague is making a deliberate effort to improve their daily routine and well-being, starting with a better cup of coffee. This small, observable act is likely part of a larger, unstated goal of self-improvement.

A Practical Workout for Your Inner Sherlock

This skill, like any other, gets stronger with practice. You don’t need a crime to solve; the world is full of stories waiting to be read.

The “1-Minute Sherlock Scan” Challenge

This is your core training exercise, adapted directly from The Observation Effect. Find a comfortable spot in a public place – a park, a cafe, a waiting room. Your mission is to conduct a 1-minute scan of a single person (discreetly and without judgment).

- Observe (30 seconds): Gather 3-5 neutral, objective details. Their shoes, their phone case, the book they’re reading, the way they hold their cup. Just collect the facts.

- Infer & Deduce (30 seconds): Ask questions. What might the worn-out soles of those expensive hiking boots imply? What story do the dog-eared pages of that science fiction novel tell? What is the most probable story that connects all these details?

Remember, the goal is not to be right; the goal is to practice the process. You are training your mind to look for patterns and connections.

The “Object Biography”

Pick a random object in your home—an old piece of furniture, a coffee mug, a framed photo. Spend two minutes writing a short “biography” of it using the 3-step scan.

- Observe: Notice its physical details—scratches, stains, fading.

- Infer: What might these details mean about its history?

- Deduce: What is the most likely story of this object’s life?

This playful exercise trains you to see that even inanimate objects are rich with history and information if you only take the time to truly look.

The World Is a Library of Unread Stories

The genius of figures like Dr. Bell, and even scientists like Alexander Fleming who observed the bacteria-free zone around mold that led to penicillin, was not in their superior eyesight but in their superior ability to process what they saw.

Most people stop at step one. They see the world but never truly observe it. By practicing the Sherlock Scan, you learn to push through to the next two steps, transforming the mundane into the meaningful.

As I conclude in my book, “The world is not just a collection of random objects. It’s a library of unread stories, waiting for a detective to come along and piece them together.” The Sherlock Scan is your key to that library.

This guide gives you the foundational framework for this powerful skill. To get the complete field guide for becoming a modern-day observer and mastering the art of deduction, you can explore the full collection of techniques and exercises in my book, The Observation Effect.