An email arrives. The subject line contains the name of a project you’ve been working on for weeks, and it’s from your boss. You open it, and your stomach tightens. The message isn’t angry, but it’s direct: “We need to talk about the direction of this project. A few things are not aligning with our goals.”

Instantly, a chaotic play begins on the stage of your mind.

The actor named “Anxiety” runs to center stage, wringing its hands and shouting about all the things you’ve done wrong. It’s quickly joined by “Self-Doubt,” who whispers that you were never qualified for this job in the first place. Then, “Anger” storms on, complaining that your boss doesn’t appreciate your hard work. Within seconds, it’s a full-blown, emotional drama, and you are lost in the middle of it—a helpless actor in a play you didn’t write, heading towards a tragic conclusion.

But what if you didn’t have to be the actor? What if, instead, you could be the director?

In our last article, we introduced metacognition as the ability to observe your own thoughts. Now, we will explore how to use that ability to consciously direct them. Stepping into the director’s chair is the most important skill you can learn for navigating the complexity of your inner world with grace and control.

The Director’s Job: It’s Not About Stopping the Play

The first and most important rule for any new director is this: your job is not to fire all the actors and stop the play. Many of us try to control our minds by fighting our thoughts. We try to suppress anxiety, wrestle with anger, and argue with self-doubt. This is exhausting, and it never works. It’s like a director jumping on stage and tackling their own actors; it only adds to the chaos.

A great director doesn’t fight the actors. They work with them. They shape the performance by managing three key areas: the casting, the script, and the set design. This is your practical framework for becoming the director of your own mind.

The Director’s Toolkit: 3 Core Responsibilities

1. The Director as “Casting Agent”: Choosing Your Focus

At any given moment, dozens of “actors”—thoughts and feelings—are waiting in the wings of your mind for their turn on stage. When you receive that critical email, they all rush on at once.

As the director, your first job is not to kick them off the stage, but to decide which actor gets the spotlight. You do this by consciously directing your attention. When you feel that initial flood of panic, the practice looks like this:

- Acknowledge the Actors: You calmly say to yourself, “Okay, I see the actor ‘Panic’ is on stage. I see ‘Defensiveness’ is here too. Hello.” You acknowledge their presence without judgment.

- Choose Your Star: You then consciously choose where to place the spotlight of your focus. “Thank you, Panic. But for the next 60 seconds, I’m going to put the spotlight on the actor called ‘Calm Breathing’.”

You are not suppressing the panic; you are simply choosing not to make it the star of the show. By deliberately placing your attention on your breath or on a simple, neutral sensation, you allow the chaotic actors to recede into the background. You, the director, decide who gets the lead role in the scene.

2. The Director as “Screenwriter”: Questioning the Script

Once the initial emotional storm has calmed, the director’s next job is to look at the script. Our automatic thoughts are nothing more than lines from old scripts we’ve been rehearsing for years. The actor “Self-Doubt” always says the same thing: “You’re going to fail.”

As the director, your job is to become a critical screenwriter. Pick up that automatic thought and analyze it. This is the practice of Thought Interrogation. Ask your thoughts critical questions, just like a writer would ask of a weak line of dialogue:

- “Is this line actually true?” (Is it 100% true that I am a failure?)

- “Is this line helpful?” (Does repeating this thought help me solve the problem, or does it just make me feel worse?)

- “What’s a more accurate or useful line?” (Let’s rewrite this. A better line might be: “My boss has some feedback. This is an opportunity to improve the project and show I can take direction.”)

By questioning the script, you stop being a passive actor reciting memorized lines and become the active writer of your own, more empowered internal narrative.

3. The Director as “Set Designer”: Shaping Your Environment

A brilliant director knows that the environment—the set, the lighting, the props—has a profound impact on an actor’s performance. It is much easier for an actor to play a calm, focused character on a quiet, organized set than in the middle of a chaotic circus.

Your mind is no different. The final job of the director is to design an environment that makes it easier for your desired thoughts and feelings to thrive. This is where you connect your internal state to your external world.

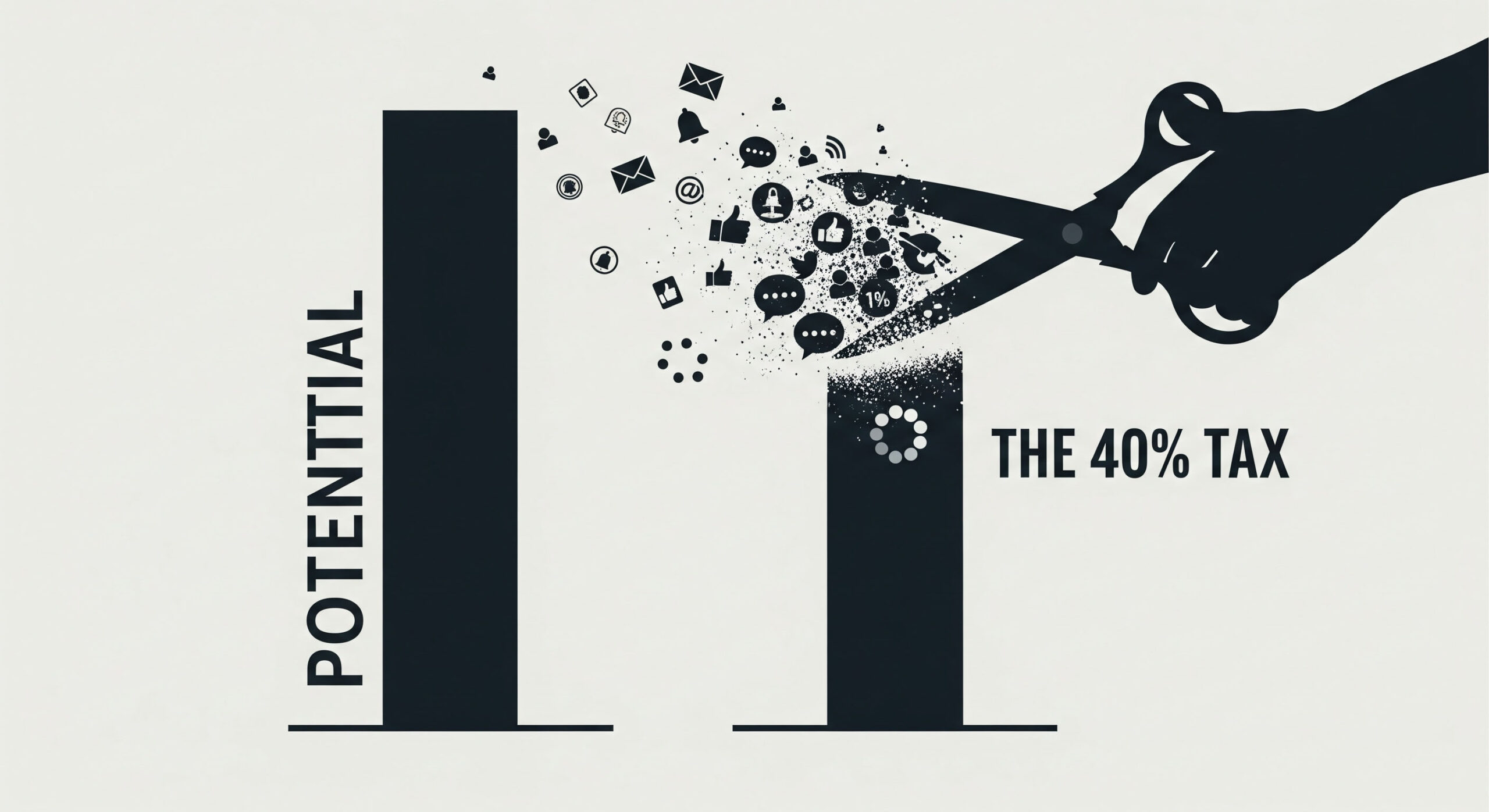

- If you want the actor “Deep Focus” to perform well, the director must design a set for it. This means turning off phone notifications, closing unnecessary browser tabs, and communicating to your family or colleagues that you need uninterrupted time.

- If you want to rehearse the script of “Gratitude,” the director can place props on the set. This might mean placing a journal on your nightstand to make it easy to write down three good things before bed.

- If the actor “Anxiety” is dominating the stage, the director can call for a change of scenery. This means getting up, leaving the stressful environment of your desk, and going for a short walk outside.

By consciously designing your physical environment, you make the job of directing your internal environment infinitely easier.

The Premiere of Your New Life

Let’s revisit that critical email from your boss. The old you—the actor—would have been swept away in a five-act drama of anxiety and despair.

But the new you—the director—handles the scene differently. You feel the initial rush of panic, but you don’t fuse with it.

- You cast your focus: “Okay, Panic is here. I’m putting the spotlight on my breath for three deep inhales.”

- You question the script: “My first thought is ‘I’m in trouble.’ Is that useful? Let’s rewrite it to ‘This is feedback.'”

- You design the set: “I can’t respond to this well when I’m feeling reactive. I’m going to get a glass of water and read the email again in five minutes.”

This is not about being emotionless or robotic. It’s about being in control. It’s the difference between being a victim of your own mental drama and becoming the celebrated director of your own life’s production.

This is a lifelong practice, and every moment of your day is a new scene, giving you a fresh opportunity to step out of the audience and into the director’s chair. To get the full “directing course,” with a complete set of tools for observation and self-mastery, you can explore the complete framework in my book, The Observation Effect.