Imagine a skilled doctor meeting a new patient. The patient says they have a headache. An unskilled observer might simply hear the word “headache” and stop there. But the doctor begins a deeper process.

First, they observe: they check the patient’s temperature, look at their eyes, and measure their blood pressure, gathering neutral data. Then, they infer: based on the data, they generate possibilities. Could it be dehydration? Could it be stress? Could it be a sign of a more serious infection? Finally, after asking more questions and running tests, they deduce the most probable cause that fits all the evidence.

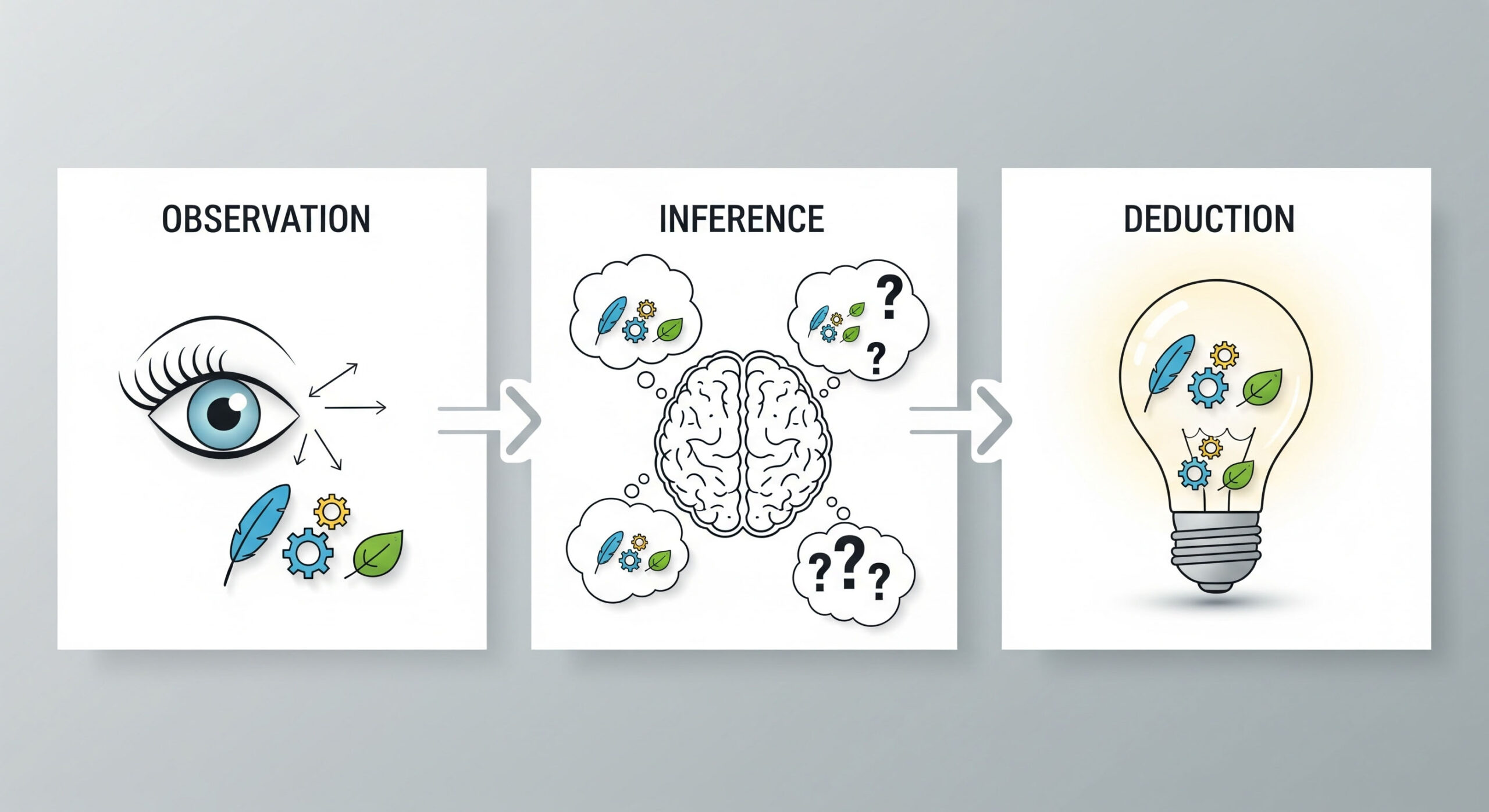

This three-step process—Observation, Inference, and Deduction—is not just for doctors or fictional detectives. It is the fundamental sequence of critical thinking. In a previous article, we introduced this as the “Sherlock Scan.” Now, this is your practical guide to turning that framework from an interesting idea into a reliable, real-world skill.

Part 1: Mastering Observation (The Art of Neutral Data Collection)

This is the foundation upon which everything else is built, and it requires a level of discipline most people never practice.

- The Goal: To collect pure, objective, and judgment-free data from the world around you. Your job is to be a camera, not a critic.

- The Common Pitfall: “Contaminated Observation.” This is the most frequent mistake. We don’t just see facts; we see them through the lens of our judgments and biases. We don’t observe “a desk with three coffee cups, a stack of papers, and an open laptop.” We see “a messy desk,” which is an interpretation, not an observation. This early judgment contaminates the entire process.

Practical Exercise: “The Objective Narrator”

This exercise trains you to separate fact from judgment.

- Choose a person, object, or scene in front of you.

- For 60 seconds, describe it out loud (or in a notebook) with one strict rule: you can only state objective facts that a camera could verify.

- You cannot use any words that imply judgment, emotion, or interpretation (e.g., messy, beautiful, lazy, happy, angry).

- Instead of: “The man looks angry.” Try: “The man’s eyebrows are lowered, his lips are pressed together, and his arms are crossed.”

This practice forces you to see the raw data the world is presenting, which is the essential first step for any clear thinking.

Part 2: Mastering Inference (The Art of Mental Flexibility)

Once you have your clean data, you can begin to explore what it might mean.

- The Goal: To generate multiple, reasonable possibilities (hypotheses) from your observations.

- The Common Pitfall: “The Single Story.” This is the trap of latching onto the very first inference that comes to your mind and treating it as the absolute truth. This is a classic cognitive shortcut of the Ghost in Your Head, and it’s the enemy of deep understanding. An expert observer never settles for their first idea.

Practical Exercise: “The ‘Could Mean’ Game”

This exercise is designed to build your mental flexibility and creativity.

- Take one clean observation from the previous exercise. (e.g., “The woman in the cafe has a laptop covered in stickers from national parks.”)

- Now, generate at least three different, plausible inferences. Start each sentence with the phrase “This could mean…”

- “This could mean she is an avid hiker and has visited these parks.” (The most obvious inference).

- “This could mean she aspires to travel and uses the stickers as motivation.”

- “This could mean the laptop was a gift from a friend or family member who loves to travel.”

The goal isn’t to find the “right” answer. The goal is to train your brain to see that any single fact can have multiple valid interpretations.

Part 3: Mastering Deduction (The Art of High Probability)

This is the final step where you move from exploring possibilities to arriving at a conclusion.

- The Goal: To select the most probable story or hypothesis that best explains all of the observed facts, not just some of them.

- The Common Pitfall: “Ignoring Contradictions.” This happens when we fall in love with our favorite inference and conveniently ignore other observations that don’t fit our narrative. A true deduction must account for all the evidence, not just the pieces that support our initial theory.

Practical Exercise: “Build and Break the Case”

This exercise trains you in critical thinking and intellectual humility.

- Look at your list of observations and your multiple inferences.

- First, “Build the Case” for what you believe is the most probable deduction. Weave the facts and inferences together into a coherent story.

- Next, immediately play devil’s advocate and try to “Break the Case.” Actively search for the holes in your own theory. Is there another deduction that could also explain the facts? Which of your observations contradicts your primary story?

This process of challenging your own conclusions is what separates a novice from a master observer. It protects you from the arrogance of a “single story” and moves you closer to the truth.

From Unconscious Bias to Conscious Insight

Let’s be clear: your brain’s autopilot, the Ghost in Your Head, is designed to violate all of these rules. It loves to contaminate observations with judgment, latch onto the first possible inference, and ignore any and all contradictory evidence. That is the path of unconscious bias.

The 3-step process of Observation, Inference, and Deduction is the ultimate antidote. It is a deliberate, structured, and conscious method for overriding your brain’s lazy defaults. It is the practical, step-by-step application of Metacognition.

This isn’t just a fun party trick for pretending to be Sherlock Holmes. It is a fundamental skill for better decision-making, deeper empathy, and more effective problem-solving in every area of your life. It is the skill of thinking clearly.

This guide gives you the training plan for this profound skill. To get the complete field manual for developing these and other advanced observational techniques, you can explore the full collection of frameworks and exercises in my book, The Observation Effect.